By Andranik Aboyan

“The chronicler who recites events without distinguishing between major and minor acts, thereby accounts for the truth that nothing which has ever happened should be regarded as lost to history.”

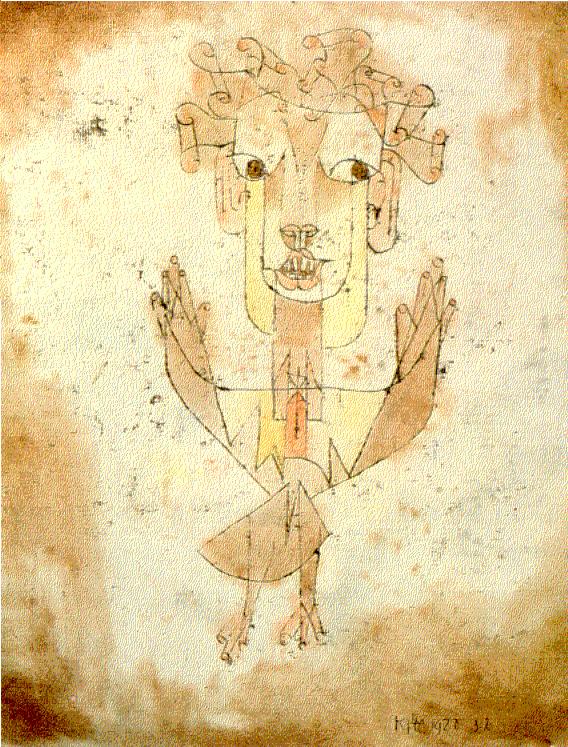

In his final work, Theses on the Philosophy of History, Walter Benjamin imagines a figure the Angel of History looking back at the past. “Where we perceive a chain of events,” he writes, “he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.” This angel wants to stay and repair the damage, but a storm called progress blows him irreversibly into the future.

Today, Armenians are caught in that same storm. We are told to face forward, to abandon the ruined memory of what has been lost the streets of Shushi, the villages of Hadrut, the soil of Artsakh and to embrace some hollow future designed not by us, but for us. Civil Contract’s vision is not of salvation, but sedation. We are not rebuilding; we are being repositioned. Not for sovereignty, but for utility.

“To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was.’ It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.

The ideology of Civil Contract is built on a hollow historicism a belief that history unfolds like a spreadsheet, that peace is inevitable if we behave ourselves, that integration into global markets will wash away the blood of Shushi and Hadrut. They speak in the sterile vocabulary of “normalization,” as if the dispossession of a people can be rendered antiseptic by diplomacy.

But Benjamin rejects this “empty time,” this idea that the past is merely behind us, and the future a straight line ahead. Instead, he calls us to “blast open the continuum of history,” to see each moment as a portal not to more of the same, but to rupture, revolution, reparation.

Armenia cannot afford to treat the 2020 war, the 2023 ethnic cleansing of Artsakh, and the corridor plans through Syunik as mere events on a timeline. These are not unfortunate detours on the road to progress they are evidence that the road itself is a trap.

“The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule.”

This is the lesson Armenians must grasp urgently. The loss of Artsakh, the normalization of Turkish-Azeri aggression, the demoralization of our armed forces: these are not aberrations. They are symptoms of a deeper illness — the loss of revolutionary time, the seduction of parliamentary gradualism in the face of existential threats.

The so-called state of exception when laws are suspended, when force replaces negotiation — has become permanent for us. We see it in how refugees from Stepanakert are forgotten; how labor rights are subordinated to foreign investment; how the national psyche is softened, cauterized, told to move on.

There is no neutral time. Either we act, or we are acted upon.

“There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

The Zangezur Corridor, praised by the ruling elite as a future economic lifeline, is precisely the kind of document Benjamin warns us about. It claims to bring development, but its foundation is built atop abandonment. It is presented as progress, yet it comes only by sacrificing our people’s presence on their ancestral land and our army’s ability to defend them.

To believe in such a corridor is to accept the terms of history’s victors to trust the same logic that erased Nakhichevan and now, Artsakh. But history is not made by the passive. It is shaped by those who refuse to let suffering be written off as collateral for someone else’s vision.

“Even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.

There is an unbroken chain of struggle within Armenian history from the fedayi of Sasun to the resistance of Sardarapat, from the workers of early 20th-century Yerevan to the youth volunteers of Artsakh. These are not romantic relics. They are signs of a people who have always resisted erasure.

Civil Contract would like us to forget this continuity. They want history to begin with them, and everything before to be written off as primitive or mistaken. But their future leads nowhere. It is not a road it is a dead end, paved with foreign capital and sealed with strategic silence.

“The Messiah does not come only as the redeemer; he comes as the subduer of the Antichrist.”

Benjamin writes that “every second of time was the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter.” For us, this means that in each moment in each village rebuilt, in each family defended, in each truth spoken we hold the possibility of redemption. But only if we refuse to forget.

Redemption, in the Benjaminian sense, comes not through waiting, but through interruption by seizing the moment, remembering the fallen, and refusing the narrative of defeat. The way forward for Armenia is not in forgetting the past but in rescuing it from oblivion. That means resisting the language of inevitability and reclaiming our history as a source of strength, not shame.

There are still forces in our country that hold fast to this idea who believe in memory as a weapon, in dignity as a duty. These forces do not measure success in applause from Brussels or Washington. They measure it in what is preserved: our land, our people, our self-respect.

“Only for the sake of the hopeless have we been given hope.”

Hope is not optimism. Hope is clarity the ability to see what is broken and choose, still, to act. Not because victory is assured, but because surrender is obscene.

That is the task before us: to redeem our history not by retelling it, but by fulfilling its broken promises. Not by trusting the storm to pass, but by learning to anchor ourselves in what is true.

And when they ask us Why do you remember?

Let our answer be clear: Because forgetting is how they win.